Veterans Celebrate Black History Month

At some point in our cultural development, we’ve gotta stop seeing each other by race, color, religion, political affiliation, economic station, etc. It doesn’t serve us well. Rather, it divides us sharply and causes even more separation and discontent.

Only the lower animals actively practice discrimination, and it leads to segregation or outright murder. We see it throughout the animal kingdom. If you wanna know what real prejudice and discrimination look like, take a long walk on the African savanna. Lions don’t socialize with hyenas; they eat ‘em. Crocodiles don’t mingle with ungulates crossing a river; they eat ‘em.

Diplomacy means the stronger or more powerful animal rules and everyone else can follow those rules. Or be eaten.

Unfortunately, the more “diverse” American society seems to grow, the more prejudicial it becomes. We receive our social training from mass media and the US government, both of whom tell us whom to love and hate.

That’s by design, but we won’t go into that here.

To anyone out there who thinks we don’t need Black diversity in our culture hasn’t been turned on to jazz or the blues, funk and rhythm and blues, southern soul cooking, and the like.

Much of our slang has its origins among the various slave immigrants to America over the past several hundred years. Our colorful language and lexicon owe a great thanks to the creative words, sayings and expressions born of strife. Our slave brothers and sisters passed down great stories that we all celebrate today, regardless of color.

When I grew up in Europe in the 1960s, we lived among people of all color and learned that the measure of a person went deeper than the color of their skin. We learned to appreciate and respect another human being for their deeds and words, and their contribution to our community.

Let’s put all this racial divide on the side of the road, if only for a month, and celebrate Black History. Since its inception, our military has always had Blacks serving in one capacity or another. When Blacks first came to America, most were imprisoned and forced into servitude. Others found their way into Native American tribes where they lived and worked as scouts and warriors.

Some—approximately 20,000—even accepted a royal invitation, Dunmore’s Proclamation, to join the British military as free men and serve in the newly created Ethiopian Regiment and the Black Pioneers. Ironically, only 5,000 Blacks served in the Continental Army.

Many of the Blacks who volunteered to serve in the British Army came from famous plantations owned by George Washington, Patrick Henry, Peyton Randolph, and other Americans who fought against the British.

In time, others joined the Corps of Colonial Marines, a group of Blacks who fought against American soldiers and civilians, most notably in the War of 1812 where they fought in the Battle of Bladensburg and assisted in burning down the White House. Blacks fighting on both sides had one common goal: fighting for their freedom and that of their kin.

Sadly, their history is long forgotten. We keep their memories alive by honoring them now.

Blacks fought in every US military war, battle and conflict in our short history, though their contributions have been whitewashed in many cases. Fortunately, their stories live on as families have passed them down to each new generation.

It is often difficult for today’s citizens to appreciate the actions of our brothers and sisters hundreds of years ago. We have no context or metric, nothing familiar to hold onto as we rummage that far back in history.

At the same time, we certainly cannot identify with how they lived and worked, how they spoke and interacted with each other. And we know they wouldn’t know what to do with us, either, with the many hundreds of new words in the English lexicon that would leave them dumbfounded.

So, wrong or not, I chose to honor in spirit all our Black veterans from all wars, battles and conflicts, but limit this article to a few contemporary heroes from WWII, what many call The Greatest Generation.

Please forgive any disrespect. It is certainly not intended.

During WWII, America was united on paper but unequal in reality. Blacks were not allowed to serve in the Marines or Army Air Corps. Even the aviation industry ignored qualified Blacks and disallowed them from working in any capacity on aircraft or in support offices.

Despite the barriers, Blacks volunteered for service wherever they could and fought to gain acceptance in their units. Blacks didn’t see themselves as descendants of slaves. They saw themselves as Americans and did what they could to prove the point.

The exploits of the best-known Black fighting unit of WWII, the 332nd Fighter Group, aka the Tuskegee Airmen, paved the way for the civil rights movement only twenty years later. The unit’s commander, Colonel Benjamin O. Davis, led his men by example:

On 24 March 1944, Col. Davis led 43 P-51 Mustangs on a B-17 escort mission deep into German territory to destroy a Daimler-Benz tank factory, located in Berlin and moderately protected by 25 enemy fighter aircraft.

Though their P-51s were not as fast as the German Me-163 and ME-262 jets, several Tuskegee pilots—Charles Brantley, Roscoe Brown and Earl Lane—shot down three German jets over Berlin, and garnered a Distinguished Unit Citation for the unit.

Davis would later become the first Black general in the US Air Force.

Air Force General Daniel “Chappie” James was a Vice Commander of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing, where my Dad served shortly after James departed to become Base Commander of Wheelus Air Base in Libya. He began his career as a Tuskegee Airman in 1943 and went on to serve in the Korean War and Vietnam War.

While Base Commander of Wheelus in 1970, then-Colonel James was faced with a major incident involving Colonel Muammar Qaddafi, whose coup had included taking over Wheelus. Well, sort of taken over Wheelus. James recalls the story:

“One day [Qaddafi] ran a column of half-tracks through my base—right through the housing area at full speed. I shut the barrier down at the gate and met [Qaddafi] a few yards outside it. He had a fancy gun and a holster and kept his hand on it. I had my .45 in my belt. I told him to move his hand away. If he had pulled that gun, he never would have cleared his holster. They never sent any more half-tracks.”

James was a badass on all levels. My Dad recalled the time then Colonel James met an arrogant white general who was touring the 8th at Ubon Royal Thai Air Base in Thailand. In their initial conversation, the general asked James who he was and his position at the unit.

James was pissed—though he didn’t display his anger—because he knew the general knew who he was, so he told the general, “I’m the MFWIC.”

The general looked puzzled.

Then James said, “Motherfucka What’s In Charge.”

The general looked up at the imposing 6’4” James who was glaring down at him, and departed smartly.

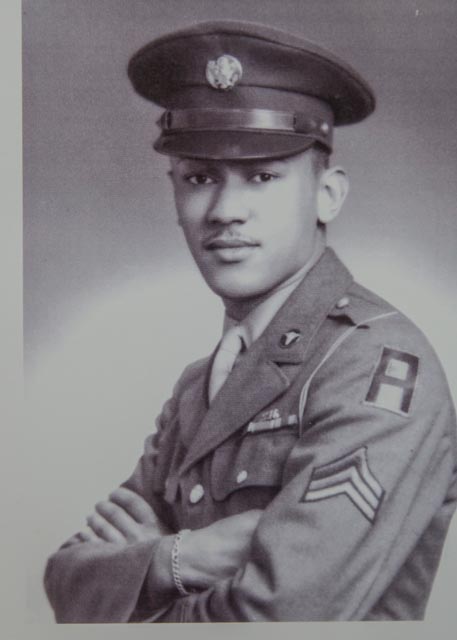

Like the millions of Blacks who served in WWII, Army medic Waverly Woodson wanted to serve his country and prove his value, not only as a Black man in a world of discrimination and hatred, but as a good human being, certainly deserving of praise and thanks.

Woodson was not the typical Army recruit: he was a pre-med student at Lincoln University in Philadelphia, and tried to become an officer but was refused because he was Black.

Undaunted, he chose to enlist as a medic and served with the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion. On D-Day, Woodson was credited with treating more than 200 allied soldiers on Omaha Beach, Normandy, even though he was severely wounded by shrapnel from a blast that killed the man next to him.

He set up an aid station and, while in great pain, tended to the needs of many men, even saving four from drowning in the heavy surf.

Like many selfless Black men whose courageous actions went unnoticed or ignored, Woodson received the Bronze Star. His commanders and fellow soldiers all agreed he should’ve received the Medal of Honor, and knew that race was the deciding factor to deny him the honor and recognition.

Curiously, PFC Desmond Doss, a white medic and conscientious objector who refused to take up arms against the enemy, was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1945, shortly after his heroic actions.

What happened to Waverly Woodson is angering to all of us who strive for racial equality, not only here in America but throughout the world. Open discrimination like this only serves to harm society.

My wish for all of us is that we celebrate the brave deeds of men and women of all colors and learn to appreciate and respect each other based on actions. After all, we call consistently good actions integrity and honor.

It is time for us to honor all our Black veterans, especially those forgotten in history, and to acknowledge that these brave souls have given us much more than jazz and blues and colorful language.

By virtue of their integrity and honor, they provide us models of excellence and set examples for us to follow.

AUTHOR: Bo Riley reports on issues of interest to veterans and active-duty personnel. He’s a former Army Ranger with the 1st Ranger Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, and lives in the Tampa Bay area.

0 Comments